Studying “Japan” with our CAAS researchers

TUFS Featured

What’s “CAAS”?

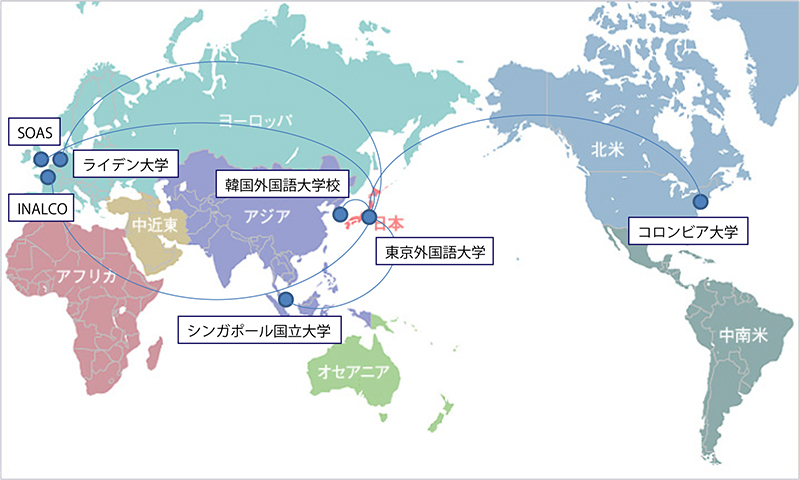

CAAS stands for “Consortium for Asian and African Studies”.

The Consortium for Asian and African Studies (CAAS) was established in March 2007 with the aim of enhancing collaboration in research and educational activities among the leading educational institutions in Asian and African Studies. The Consortium now encompasses seven higher educational institutions worldwide, including TUFS.

Asia and Africa have been acquiring growing importance as key-players in the era of globalization. Due to the regions’ high degree of diversity, however, single educational institutions have faced limits in terms of covering Asian and African Studies in the necessary breadth and depth. The corresponding need for interinstitutional collaboration, especially that of an international nature, led to the Consortium’s formation. Through this new international coalition framework, the seven institutions with their long traditions and high levels of professionalism in the fields take advantage of their synergy in order to explore new frontiers.

Member Institutions:

– Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO), France

– Leiden University, the Netherlands

– Hankuk University of Foreign Studies (HUFS), Republic of Korea (Joined in March 2011)

– Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) of National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore

– School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (SOAS), U.K.

– Columbia University, U.S.A.(Joined in April, 2010)

– Tokyo University of Foreign Studies (TUFS), Japan

TUFS’s stated missions are to “establish itself as a leading educational and research institution in the areas of Japanese Language and Japan Studies as seen from an international perspective”, and to “globally disseminate research findings from studies on Japan and the international community and cultures”. With the help of funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), awarded to universities proactively contributing towards reforms, TUFS focusses on global Japan studies as a part of its functional enhancement project inaugurated in the fiscal year 2015.

By inviting a core CAAS unit of prominent scholars in the fields of Japanese Language and Japan Studies, we will foster Japanese researchers with a global perspective and establish TUFS as an international platform for Japan Studies.

What are the CAAS Unit researchers’ areas of interest and expertise? (Interviews)

Discovering Japan through folk song

Dr. David Hughes (SOAS, University of London)

I have been based at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, UK, for almost 30 years, though I’m retired now and am a Research Associate. My main research fields, geographically, are the traditional music of Japan and the traditional music of Java. I also research the methods of musical transmission in many different countries. My interest in Japanese folk song (min’yō) began in 1972 when I discovered a wonderful collection of field recordings in the library of the University of Michigan. Since 1977 I have visited Japan many times for fieldwork and other projects; in total, I have lived in Japan for more than ten years. I am very happy to return to Japan to be a visiting lecturer at TUFS as part of the initiatives of the Consortium for Asian and African Studies (CAAS). TUFS is wonderful!

My research also includes performing folk songs myself. I have been playing the shamisen for over 40 years, and I also play the shinobue (bamboo flute) and various Japanese drums. Naturally I have also learned to sing folk songs. Because I was virtually the only non-Japanese performing traditional folk songs and folk shamisen at the time, from 1977-81 I performed more than 40 times in Japan on television, stage and radio, and I was also sometimes an MC or a judge at folk song contests. (I hate being a judge: I just want people to enjoy the music without being judged!) In my classes, I will try to teach my students a bit of folk singing, and as we listen to recordings we will explore the meanings within their lyrics and the Japanese traditions and practices that inspired them.

But to provide a broader sense of music in Japan, I will also teach the students a little about Okinawan music, including trying to play the sanshin. To give them an even better live experience, I am also taking them to a folk song club (min’yō sakaba), an Okinawan music class at an Okinawan restaurant in Fuchū, and to the Charanke Festival in Nakano, which features both Okinawan and Ainu music, dance and food! And a former TUFS student, now teaching at Gakugei University, will give a lecture about her research on the music of the Korean and Chinese communities in Japan.

As you might sense from the phrase Min’yō wa kokoro no furusato (“Folk song is the heart’s home town”), folk songs have been an expression of the lifestyle, customs, and ways of thinking of the Japanese through the ages. There are many types of folk songs—from festival songs and dance songs for the ancestral O-Bon festival to the songs of travelling entertainers—but I would like to focus in particular on “work songs,” such as Hokkaido’s Sōran Bushi, the songs of herring fishermen pulling in their nets, and Tottori’s Kaigara Bushi, the song of scallop fishermen. These were originally sung by the fishermen without accompaniment, to keep up an efficient rhythm or help them forget the strain as they worked. The songs were then given accompaniments with instruments such as the shamisen, flute, and drums, and further refined for performance on the stage. There are many local “preservation societies” (hozonkai) that strive to keep old folk songs alive in their original form.

It is really a shame that many Japanese university students and other young people in Japan today know relatively little about Japan’s folk songs. It is indeed important for Japanese students to look beyond Japan and support globalization, but we also need to know the culture and customs of our own country in order to understand those of others. At SOAS more than half of the students are not from the UK, and one third of the faculty members are from overseas. TUFS may not have quite as high a number of international students and staff, but I think that it displays the highest level of diversity among universities in Japan. I would like to see students place themselves in such an environment and delve deeply into the study of Japan and the world from various different perspectives.

Rethinking Japans past and future through the movies

Dr. Iris HAUKAMP (SOAS, University of London)

I studied and researched Japanese film at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and joined Tokyo University of Foreign Studies under the Consortium of Asian and African Studies (CAAS) programme in October 2015. My main research interest is the Japanese film from the 1920s to the 1950s, with a particular focus on the film director Itami Mansaku.

Itami is known to many people as the father of famous director Itami Juzo (e.g. “The Funeral”, 1984), but clearly the elder Itami should be acknowledged in his own right as a director, scriptwriter, and social critic, crucial for our understanding of interwar and postwar intellectual and cinematic discourses in Japan. By reading his numerous essays and articles, and watching his films, we begin to understand the extent of his calm and realistic observance and precise criticism of these days’ society. In his essay ‘The question of those responsible for the war’ (August 1946), published only a year after Japan’s surrender, he insisted that ‘being deceived is already a sin in itself’, and thus foreshadowed subsequent discussions about universal victimhood or individual responsibility.

He was known as one of the best scriptwriters of his time, but his output as a director was relatively low, also due to his serious health problems and his premature death of tuberculosis in September 1946. The films he did direct, however, were very popular at the time. In one of his masterpieces, “Akanishi Kakita” (1936), based on the Edo-period Date Rebellion, star actor and producer Kataoka Chiezō actually plays two roles. With the film’s final scene being anachronistically underscored by Wagner’s “Wedding March”, it was an adventurous production.

By 1936, when “Akanisha Kakita” was released, the so-called Manchurian Incident had occurred, and the military planned further expansion into China. Itami’s films display a distinct dislike and criticism of the militarism and the accompanying ideologies of the era. Film reflects the social discourse of its time, and at the same time we can also discern the filmmaker’s attitudes towards these trends. In my own research of Japanese wartime film, I am interested in how people actually navigated through these complex times, and also in further understanding the medias’ role in times of (armed) conflict.

Currently, what has been titled the refugee crisis, triggered by the civil war in Syria, shakes socio-political discourses in Europe. Thinking about the use of the media, both by IS and in those countries displaying an increasing reluctance to take in refugees, it reminds one of the situation before the outbreak of the last war on a global scale. This is clearly something that needs to be observed carefully.

In my undergraduate class beginning in April, we will study three Japanese wartime films, including detailed analyses of cinematography, plot, and the background of their production and reception. Studying and improving our understanding of the mutual interaction of media, politics, and society will, I hope, provide the opportunity to look at Japan’s past, present, and future from yet another angle.

To Promote the Mutual Understanding between Korea and Japan via Intercultural Communication

Dr. Park Yong Koo (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies)

1.Research Interests and Teachings at TUFS

The international relationship between Korea and Japan cooled down. While it is true that the most recent cooling off has been occasioned by disagreements about “History and Territory” between the two countries, it remains vivid in my memory that its source goes far back into the 1982 incident of Japan distributing history textbooks that were deem to include distorted historical facts about Korea. This happened when I was a sophomore at HUFS, and I inquired about the reason why this kind of problem occurs.

My inquiry led me to consider the contrast between the historical facts and their interpretations. I came to realize that the trouble lies not so much in the facts but rather in their interpretations. The discussions on the relationship between Korea and Japan cite various sources and documents, but even the identical material affords contradicting interpretations, depending on whose side one is on. The root of it all, I think, has to be distrust about the opposing party. This recognition developed into my research interest on the mutual understanding between Korea and Japan. My research in this respect has been to study the mutual understanding and their discrepancies between the two countries and the sources. One of the results from my research has been that the cool breeze between the two countries cannot be studies without also including countries like China and more broadly the Eastern Asian countries. The outcome was to develop a course, entitled “Mutual Understanding among Korea, Japan, and, China” and I offered it thankfully at TUFS.

Another course that I offered was “Theories on the 21st Century Japanese.” The research I have been conducting on the mutual understanding between the two forced me to realize that Korean and Japanese are alike, yet they are also quite different, and the differences remains fresh in my mind. Theories on the thinking of Japanese and their ways of doing things became the focus of my research. The course title “the 21st century” indicates that the theory that encourages to see Japanese as being “collective” has had its time, but the 21st century is the time to move on from this old paradigm.

Between the two courses that I offered at TUFS, the 21st century Japanese is more aligned with my current research than the mutual understudying course. It is certain, though, my researches are geared toward getting rid of misunderstanding between Korea and Japan. And this is ultimately to harmonize the communication between the two countries through intensifying their mutual understanding.

2.To Strengthen Japanese Dispatch Capabilities

Adoption of the foreign cultures and the localization processes highlight the history of Japan. Korea and China for the ancient Japan, European countries for the modern Japan, and America for the contemporary Japan has been the old sources of unique Japanese culture with sophistication. Japan, one of the wealthiest countries in the world currently owns an appropriately rich cultural contents, living up to its size of economy. It surprises no one that Japan wishes for a stronger dispatching capabilities and powers amongst international countries and their groups. Nonetheless, such capabilities are of less importance than the dispatchable contents. This is so because the dispatching power will be determined not merely by the dispatching frequencies, but also by the willingness at the receiving parties. It is then incumbent to develop the internationally circulating dispatchable content, making good use of the Japanese culture’s unique merits that were shone through the processes of adoption and localization of foreign cultures. I anticipate your active participation on promoting the communication among Japan and the communities of the world at the Unit of CAAS, where the scholars and researchers take part in.

3.My Impressions of the TUFS and the TUFS students

The campus, while it cannot be said that it is huge, its building and their arrangement have a lot to be said about. Of these, I am most impressed with the fact that campus buildings are placed in such a way that they are all connected. This placement of buildings kept me dry even on those days of heavy rain on my walk to the dorm. My semester here allowed me to interact with many students from overseas. The growing number of the TUFS students going oversea to study indicates to me that TUFS is evolving into one of the global institutions of higher learning. All of the graduate students in my seminars have had experienced life in other countries, and they participated in the class by expressing their views, basing them on their own experience. The students who are studying diligently at the library were not the only ones on campus. There were also those who were participating various physical activities on campus. I would without hesitation name TUFS a “small but very strong global institution of higher learning.”

4.The Strengths and the Deficiencies of Japan, Seen Without

Koreans view Japan as having two sides: (1) Japanese are kind, diligent, and courteous, but (2) Japan is militant, nationalistic, and suffers from hegemonism. They feel more affected with the Japanese than they do with Japan the nation. I might add, focused on the theories of Japanese the following. The high context culture of Japanese, which preferrers the communication via mood—rather than it via words—can be difficult to foreigners.

Knowing Japan from questing of history

Dr. Ethan MARK (Leiden University)

Since finishing my PhD in the field of modern Japanese history at Columbia University in New York, I have been teaching at Leiden University in the Netherlands. My research is focused on the experience of modern Japan and its empire before and during World War Two–along with the legacies of this experience in Japan and across Asia. I’m particularly interested in the experience of the Japanese occupation of Indonesia (1942-1945). In my PhD thesis and my new book which will be published in 2017 (The Japanese Occupation of Indonesia: A Transnational History) I explore the complex wartime interaction between Japanese and Indonesians and its evolution before, during, and after Japan’s occupation. I focus on Japanese civilians who accompanied the army as propagandists (「文化人」), and Indonesians who chose to collaborate with them hoping that Japan would live up to its promise to “liberate Asia from Western colonialism.” The story is tragic but also fascinating, and very important for subsequent Asian and global history.

My ongoing research on Japan’s experience in Southeast Asia has also inspired me to think about the history of the Second World War from a global and comparative perspective. I think looking at the war from an Indonesian perspective, for example, yields new and very important insights into the war’s global dimensions. When the Japanese invaded Indonesia in 1942, Indonesians had been suffering under Dutch colonialism for several hundred years. For this reason they did not see the war the same way as the Europeans or Americans saw it—as a struggle between democracy and fascism, for example. Rather, they saw and experienced the war as a struggle between competing imperial powers—Japanese and Western—and they hoped to take advantage of the situation to build a new and independent nation. The Japanese, for their part, realized that in order to win the war, it was necessary to try to convince Indonesians and other Asians to cooperate with them—they could not afford to repeat the disaster of their war in China. So each side tried to use the other side for their own purposes. If we look around the world during World War Two, we see the same sort of complex situation in many places, such as British India, North Africa, even in Korea and Taiwan: local people caught in the middle between the competing Allies and Axis powers and suffering from it, but also trying to take advantage of the situation to achieve improvements in their lives and national independence, and the imperial powers meanwhile adjusting their rhetoric to try to win local hearts and minds to their side. Over the course of the war, you can see the impact of these sorts of struggles on the thinking and rhetoric not only of Indonesians, Indians, and Africans, but also Americans, Europeans, and Japanese. In this sense, in terms of global history, World War Two was truly a war about the fate of empires and the rise of independent nation states. This is a story that most conventional histories of the war do not pay enough attention to because they are focused on the experience of the combatants—the Americans, the Europeans, and the Japanese—and not enough on the experience of the great majority of the worlds’ population who were “in-between.”

This is the kind of global perspective that I enjoy developing not only my research, but in my teaching. At TUFS (as well as at Leiden) I offer courses about Japan’s and Asia’s experience during the 1930s and 1940s, along with the memory of these experiences, from a global and comparative perspective. I think it is very important to continue to explore this history, not only because the war experience continues to have a great impact upon Japan’s relations with its Asian neighbors in particular, but also because understanding the complex nature of such phenomena as imperialism, fascism, and nationalism in the past helps us understand the forces that are shaping the present in Asia and around the world.

Let’s learn about Japan from international Japan Studies

CAAS professors’ classes within the Japan Studies program

The Institute of Japan Studies invites prominent and innovative researchers from the CAAS Unit and offers some fascinating classes.

FY2016 Fall Quarter

- Japanese Modernity 1

Lecturer:

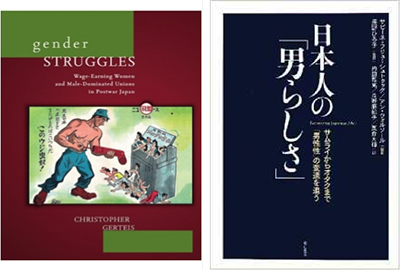

Christopher GERTEIS(SOAS) Major: History

Overview of the course:

This course examines the historiography of early modern and modern Japan with particular emphasis on the nexus of social and economic change from the Tokugawa to the Taisho and early Showa era (1600 to about 1930). By addressing the question of the relationship between early modernity and the radical transformation to industry and empire experienced by Japan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, students will read and discuss in-depth to the historiography of English language scholarship published alongside Japan’s rise to prominence as a global power.

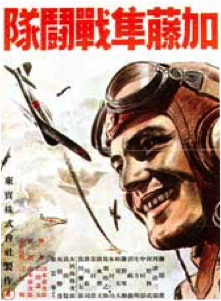

- Japanese Wartime Film: Politics of Representation/Representation of Politics

Lecturer:

Iris HAUKAMP(SOAS) Major: Film studies

Overview of the course:

This course considers the relation of film and history by conducting an in-depth analysis of Yamamoto Kajirō’s fighter pilot film Katō hayabusa sentōtai (Colonel Kato’s Falcon Squadron, 1944). The film is representative of kokusaku eiga (‘national policy films’), was highly awarded, and became part of the public’s. cultural repertoire. In terms of local history, Chofu airport hosted ‘special attack units’, and various kokusaku eiga were produced by local film studios.

Each week, we will consider the film from a different perspective and thus will slowly build our own narrative of this particular film project and the time of its production and reception. The course will result in a collaborative, full exploration of the film and its background, resulting in a website dedicated to our findings.

FY2016 Winter Quarter

- RETHINKING MODERNITY: JAPAN AND WORLD HISTORY

Lecturer:

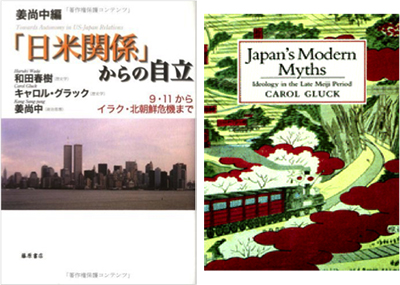

Carol GLUCK (Columbia University) Major: History

Overview of the course:

The course seeks to place modern Japanese history in a global context, with the larger goal of rethinking concepts and definition of modernity. Modernity is approached as a historical process that began in sometime in the 18th century and continues to this day. What is modernity? How is it experienced in different times and places? How should we understand Japan’s modernity in terms of the commonalities and connections in modern experience around the world?

FYI: Invitation schedule for CAAS researchers

- Christopher GERTEIS (SOAS) [2016 fall to 2017 spring]

- Iris HAUKAMP (SOAS) [2016 fall]

- Carol GLUCK (Columbia University) [2016 winter]

FY2017

- Timon Screech (SOAS) [2017 spring and summer]

- Oshikiri TAKA (SOAS) [2017 summer]

- Moon Myung Jae (HUFS) [2017 summer and fall]

- Bernard Thomann (INALCO) [2017 fall and winter]

- Carol N. Gluck (Columbia University) [2018 winter]

Past classes

- Park Yong Koo (HUFS) [2016 spring and summer]

- Ethan MARK (Leiden University) [2016 summer]

- David Hughes (SOAS) [2015 winter]